musing at the confluence of data, software and security

by Earl Chen

Raising the Bar, NIST Password Updates

30 September 2024In NIST parlance, SHALL NOT carries the weight of a decree. You should obey the rule and disobeying has significant consequences. SHALL NOT means the behavior must be avoided and avoidance is mandatory. In the NYC subway system, you SHALL NOT touch the third rail. Climbing from the safety of the subway platform onto the tracks and then reaching down and wrapping your highly conductive fingers around the energized third rail that powers subway cars will end in immediate spectacular death. A very serious consequence for doing when the guidance is SHALL NOT.

According to NIST, SHOULD NOT means the behavior avoidance is highly recommended, but not mandatory. Continuing the NYC subway analogy, you SHOULD NOT jump the turnstiles. If you get caught you will be ticketed and perhaps even arrested. If you violate the SHOULD NOT jump the turnstile rule, there are consequences, but the consequences are not life threatening.

I’m not sure when software and security professionals decided that SHOULD NOT became synonymous with SHOULD NOT CARE, but when it comes to passwords, that has been the case for years. Several news outlets are making noise that the latest NIST SP800-63B draft has two password behaviors that have finally moved from turnstile jumping SHOULD NOT to third rail touching SHALL NOT. Even though SHOULD NOT is a strong recommendation, maybe finally SHALL NOT will help raise the bar.

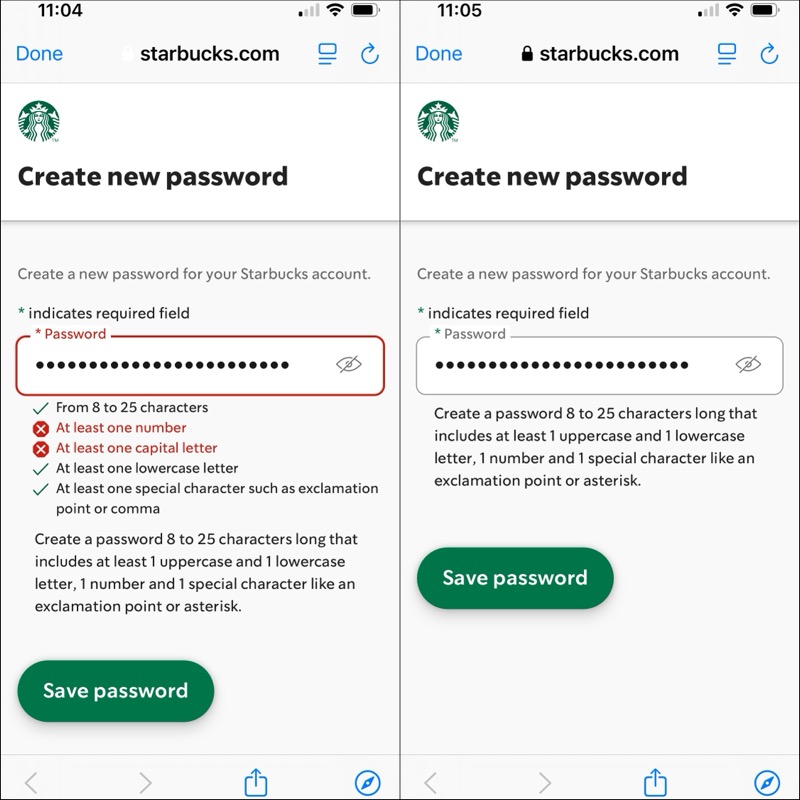

For years, decades really, we’ve been subjected to software that imposes arbitrary password complexity requirements. These complexity requirements are not supported by any evidence that they improve passwords yet they have persisted and are even enforced by erstwhile security experts. Some of my favorites are:

-

Must include a special character. Each and every site has a different set of special characters. A separate issue is that spaces are never included as one of the special characters, but that is a topic for another day ….

-

Must include at least one numeric character.

-

Must include at least one upper and one lower case character.

-

Must not include any repeated characters or characters in sequential order. Huh, really?

These are still commonly found on many sites despite NIST’s very clear guideline which has been published since 2017:

Verifiers SHOULD NOT impose other composition rules (e.g., requiring mixtures of different character types or prohibiting consecutively repeated characters) for memorized secrets.

Yes, the language is SHOULD NOT, so while it is a good practice to not enforce ridiculous password complexity rules, the practice is still permitted. Not recommended, not a best practice, not a good practice, but still permitted. Now the guideline is moving to SHALL NOT meaning the practice is no longer permitted:

Verifiers and CSPs SHALL NOT impose other composition rules (e.g., requiring mixtures of different character types) for passwords.

Let’s see how quickly those rules disappear. More importantly, I am interested to see fewer assessments from check-the-box security gatekeepers that call out “missing” password complexity requirements.

The second guideline changing from SHOULD NOT to SHALL NOT is this beauty:

Verifiers SHOULD NOT require memorized secrets to be changed arbitrarily (e.g., periodically).

Will now read:

Verifiers and CSPs SHALL NOT require users to change passwords periodically.

Aside from forcing users to change their passwords for no reason, periodic password resets encourage terrible user behavior. I’m reminded of a company where certain approvals required action by a specific senior-level manager, Vance (name changed to protect the guilty). Vance was going to be away on vacation, so he gave (different, but also problematic behavior) one of his direct reports (let’s call the direct report Jimmy) his password so the approvals could be completed on time. Jimmy noticed that the password was composed of a word followed by a two-digit number. The following month, Jimmy incremented the two-digit number, tried the revised password, and… it worked! Jimmy now had perpetual access to Vance’s managerial account. I remember Jimmy became concerned when the digits were about to roll over from 99 to 100. He wasn’t sure how the password would be changed, but Vance dutifully just started the two digits back at 00 and Jimmy’s inadvertent access continued.

The migration away from these nonsensical rules should have occurred years ago. SHOULD NOT has sufficient weight to force reasonable and orderly migration toward better and more secure system behavior. Unfortunately, that was not the case, but now the evolutionary change from SHOULD NOT to SHALL NOT will hopefully have the desired effect and rid us of these outdated password practices.

tags: security